105+ Ways to Make Better Decisions in Politics With Mental Models

Make wiser decisions in politics, learn like a pro and thrive with AI

Here's an overview of the article:

What & Why of Mental Models

Three Benefits of Using Mental Models:

Make Wiser Decisions

Learn Like A Pro

Succeed With AI

How To Use The List of Mental Models

105 Mental Models

30 Mental Models for Strategy

30 Mental Models for Communication

45 Mental Models for Personal Effectiveness, incl. Cognitive Biases

Three Books That Blew My Mind Open To Mental Models

Coming Soon: My Free Pre-Prompted "Mental Models for Politics" GPT

What & Why of Mental Models

Mental models are everywhere.

But only few people are aware of them.

Even fewer people know how to take advantage of them.

You use models all the time:

You use your phone's map to navigate to a new place.

You check the weather forecast to know if you need an umbrella.

You use a book's table of content or index to get an overview or find information.

Models are a representation of something else: a city's geography/streets, the weather, or the book's content. You use them to understand, explain, predict more complex systems.

Mental models are similar, only that they are an internal representation of an external reality. You use them to understand, explain, predict, interact with the world around you.

You use mental models all the time:

You plan for a rainy versus a sunny weekend (Scenario Planning)

You take negative feedback as sign that you are simply not good at the task (Fixed/Growth Mindset)

You preempt other people's reactions to your new idea (Game Theory)

Mental models typically work unconsciously. You take your mental models for granted, most of the time. That's what makes them useful: you're using them even while not putting much attention on them and you can instead focus on something else.

But every now and then, this way of doing things fails you:

You apply a mental model in the wrong context.

You oversimplify and overuse a mental model, and get stuck in limited choices.

You miss important information, because you do not have mental models that could make sense of them.

Instead, here are the benefits of becoming aware of the mental models you use and learning how to deliberately apply them:

Make wiser decisions

Learn like a pro

Succeed with AI

Three Benefits of Using Mental Models

Make wiser decisions

I know: 'wisdom' and 'wiser decisions' sounds grandiose.

But: Aristotle talked of 'practical wisdom' (in Greek: phronesis). Part of practical wisdom is the balancing of competing perspectives and making contextual/situational judgments.

That is, in part, a creative exercise: you need to uncover, use and draw implications from diverse perspectives. Mental models allow you to do that.

How? By consciously and freely switching between mental models.

You've heard (and maybe said) this before: 'Think outside the box'.

The problem is: that's really difficult. Your brain likes to think in boxes.

If you try to think 'outside the box', what you are actually doing is thinking in another box.

Imagine this: you get your team together to brainstorm ideas for how to increase your campaign's visibility. So far, all ideas sound familiar, they revolve around what's typically being done in politics to increase visibility.

Then, someone says: 'Let's think outside the box...I don't know... what would we do, if we were not in politics? How would Elon Musk create visibility? How about a 5-year old? What would your grandma say?'

If you're lucky to have someone like that, great! They've just helped you switch boxes. You started in a 'politics' box and then moved to the 'Elon Musk', '5-year old' and 'grandma' boxes.

That's - simplified - the creative process:

Define your problem - challenge and refine it

Diverge - switch to different boxes from which to generate ideas & insights

Converge - prioritize, analyse, decide

You consciously diverge in your thinking before converging on a decision. Mental models help you diverge. And this divergence is a critical part of making wiser decisions.

📚 If you want to learn more about the creative process, I recommend Luc De Brabandere and Alan Iny's book 'Thinking in New Boxes' (these articles and book brief are a great intro).

Learn like a pro

“Well, the first rule is that you can’t really know anything if you just remember isolated facts and try to bang ‘em back. If the facts don’t hang together on a latticework of theory, you don’t have them in a usable form. You’ve got to have mental models in your head. And you’ve got to array your experience, both vicarious and direct, on this latticework of models.” Charles Munger, Warren Buffet's business partner

You remember in relation to existing memories, knowledge or 'schemas', i.e. structures that new information can be linked to. It's part of the reason we typically don't have memories of early childhood: as children we simply have fewer existing 'schemas' that new information could attach to in order to be stored long-term.

Learning develops these schemas. Learning is making an internal model of the external world. As you learn and have more & richer internal models, it becomes easier to make sense of new information. You then adjust the models, seek to minimize error, bring the models in hierarchy etc.

The way you do this is in stages, or rather a loop:

Attention

Active engagement

Error feedback

Consolidation

When you actively consider how to use a mental model, you move them from the unconscious back to the stage of active engagement. You try them out, get feedback, repeat, and over time, the mental model will be consolidated and become unconscious again.

This process of consciously considering your mental models is key to becoming better, if not a 'master', at navigating in your domain, be it decision-making, your relationships, communicating etc.

This is a key lesson from Anders Ericsson's work on the 10,000 hour-rule: to achieve mastery in any domain, roughly 10,000 hours of deliberate practice are required. It's not the time itself and it's not any time spent on a skill. If you perform a skill unconsciously, it means that you are performing it efficiently, but not necessarily at a high level. Often, we consolidate our learning at a level that is OK, enough to get by; it's typically when we have reached a plateau.

You could have a career exceeding 10,000 hours, but still be mediocre at the skills involved in your work, because you did not engage in deliberate practice, or as the saying goes: you do not have 10 years of experience, but 1 year of experience repeated 10 times.

It's time spent on deliberate practice that improves, i.e.:

focused on technique,

being goal-oriented, and

getting constant/immediate feedback.

Great athletes obsess over their swing, or their stride.

Great chess players tirelessly analyze and memorize openings and endgames of grandmasters.

Great decision-makers obsess over using decision-making frameworks, considering the decision-making process as well as obstacles, e.g. in the form of cognitive biases.

Great learners actively expand, use and get feedback from their mental models.

📚 Check out a free copy of Charlie Munger's 'Poor Charlie's Almanack' here.

Succeed with AI

Three ways that mental models help you succeed with AI:

First, prepare yourself. Think through what AI development means for you and your work. I first saw the link between AI and mental models through Michael Simmons' work: in a nutshell, you could follow the latest AI news and try out the hottest tools, but still not be smarter. Development is fast, exponentially so. Trying to make sense of AI on the level of new facts & tools is going to be overwhelming. Instead, considering AI development through the lens of a few mental models gives you a more solid foundation for understanding and preparing for AI.

Second, know who you are. Mental models are a tool, yes. But let's not forget that they are also an intimate part of who you are. They are how you make sense of the world. In turn, they are shaped by your life experiences, much of it implicit lessons-learnt, beliefs, personal philosophy, and yes, also what you have explicitly learnt. They are also shaped by biology (if we consider cognitive biases as mental models). Your mental models are part of the idiosyncrasies that make you you.

Is AI smarter than you? Different measures show: it's getting there or surpassing you already.

Is AI emotionally smarter than you? Again, it's getting there, see here.

Is AI smarter than all of us, together? That's what Artificial General Intelligence implies and billions of dollars are pouring into developing it right now (see OpenAI's mission), so: maybe soon?

Is AI like you? This is where it gets philosophical very quickly. My take: I doubt it, even if it can simulate parts of you already (your voice, your memory, your appearance).

Third, augment yourself. With mental models you can use Generative AI more deliberately:

Use mental models to understand what GenAI can and cannot do.

Make sense of GenAI output by looking at it from the lens of different mental models.

Prompt GenAI to develop options regarding your challenge using multiple mental models.

How to use the list of mental models

"All models are wrong, but some are useful" George E. P. Box

Each of the following models is 'wrong' in that it only captures part of the chessboard. To expect more of it would be to confuse the map for reality. The value of a model is not in capturing reality. The value of a model is in using it to better navigate reality.

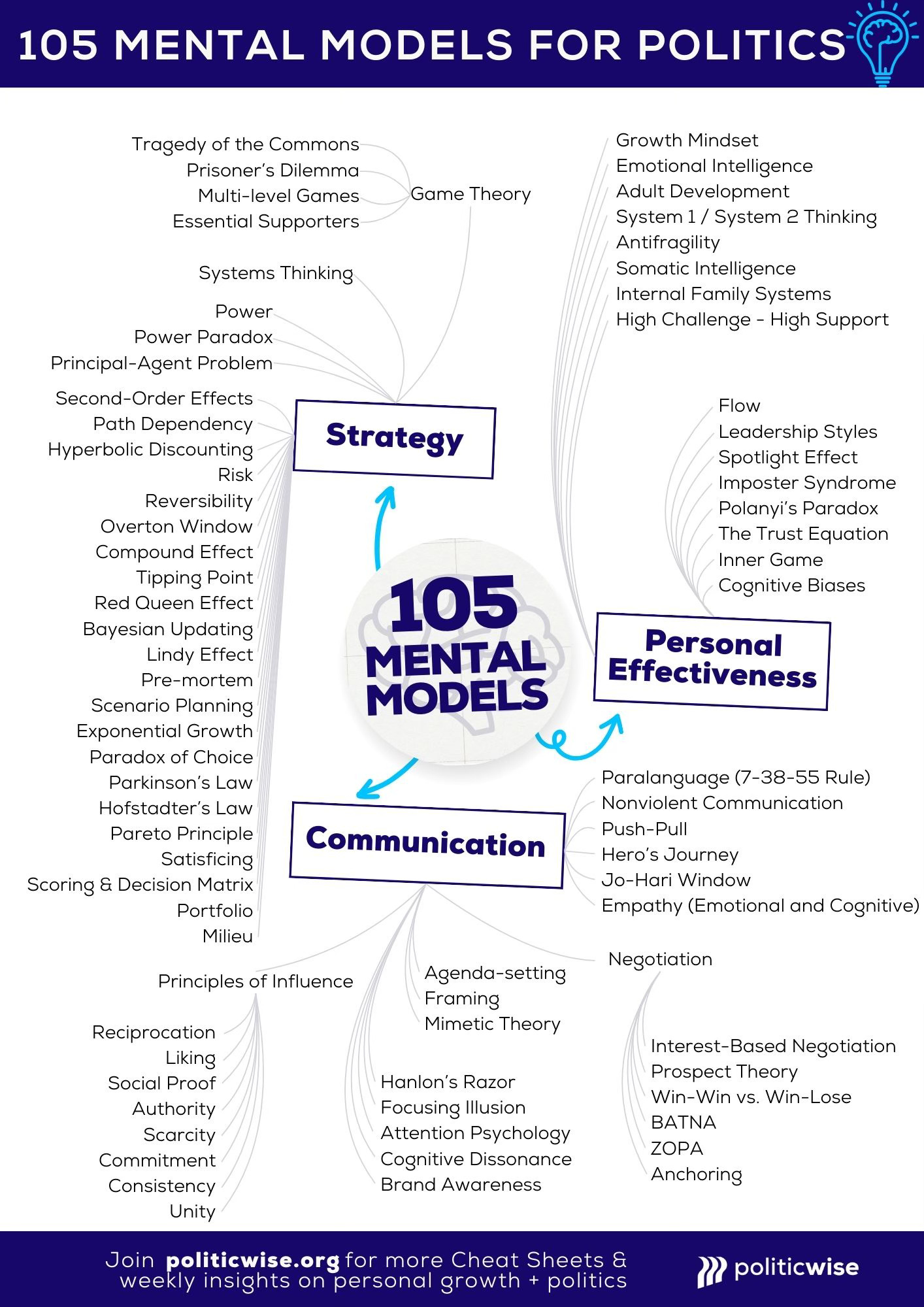

Below, I've pulled together key mental models in three areas:

Strategy

Communication

Personal effectiveness

Some of the models have fully-fledged theories behind them, others are specific concepts from a variety of disciplines. I've selected them for relevance in politics, but they are domain-agnostic, they'll be useful beyond politics.

The list is also necessarily incomplete.

My suggestion on how to use this article:

Skim through the list of mental models

Recognize mental models that you are familiar with. It's good to notice the ones you are already using

Which mental models pique your curiosity? Take a note and see which one you want to research more

Use AI as a sparring partner. I built a pre-prompted GPT to help me consider some of my decisions through the lens of mental models.

As you start using mental models more explicitly, the key question to consider is:

🤔 What can different mental models teach me about my problem or decision?

105 Mental Models

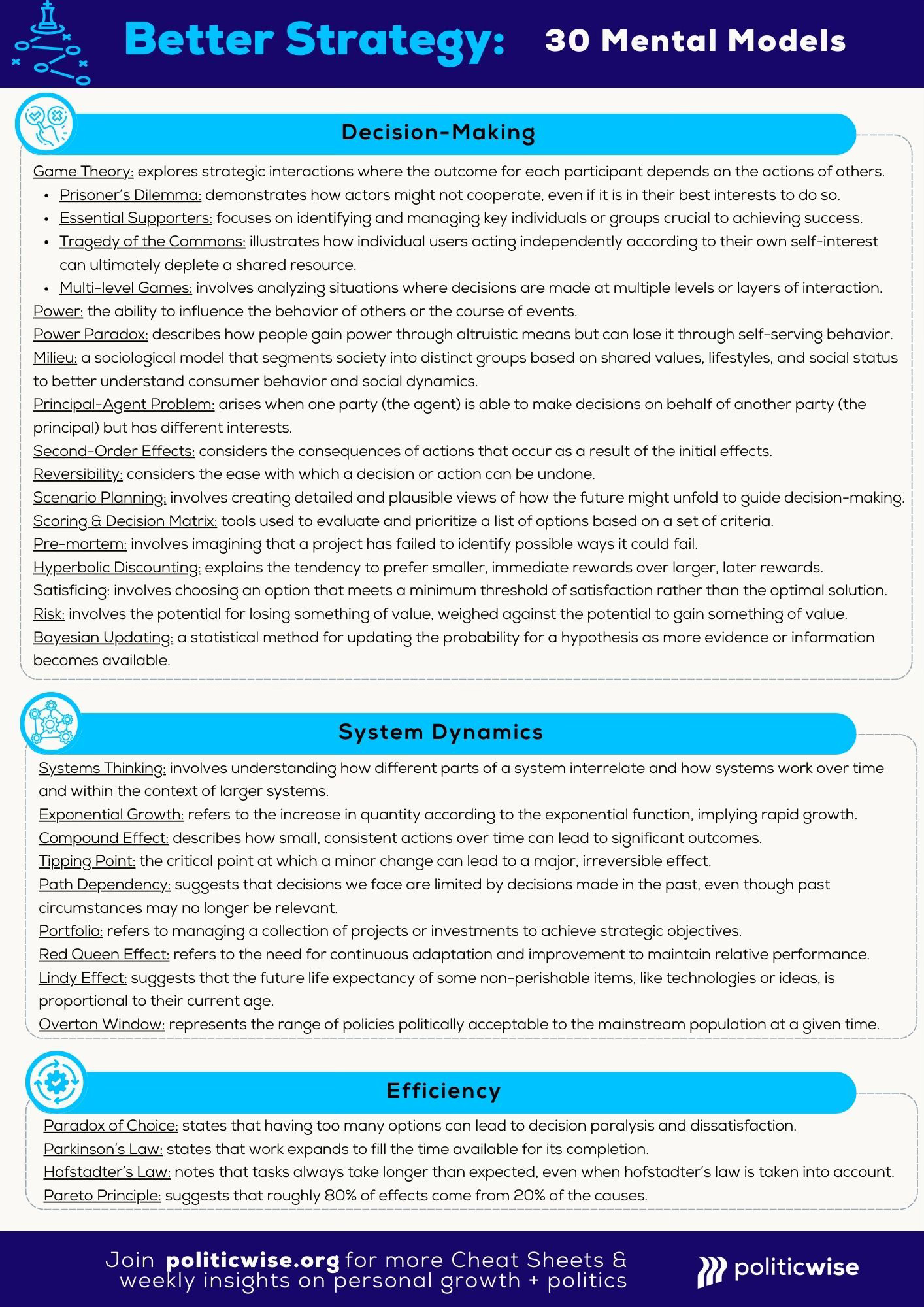

30 Mental Models for Strategy

Game Theory: explores strategic interactions where the outcome for each participant depends on the actions of others.

Tragedy of the Commons: illustrates how individual users acting independently according to their own self-interest can ultimately deplete a shared resource.

Prisoner's Dilemma: demonstrates how two individuals might not cooperate, even if it is in both their best interests to do so.

Multi-level games: involves analyzing situations where decisions are made at multiple levels or layers of interaction.

Essential supporters: focuses on identifying and managing key individuals or groups crucial to achieving success.

Systems thinking: involves understanding how different parts of a system interrelate and how systems work over time and within the context of larger systems.

Power: the ability to influence the behavior of others or the course of events.

Power Paradox: describes how people gain power through altruistic means but can lose it through self-serving behavior.

Principal-Agent Problem: arises when one party (the agent) is able to make decisions on behalf of another party (the principal) but has different interests.

Second-Order Effects: considers the consequences of actions that occur as a result of the initial effects.

Path Dependency: suggests that decisions we face are limited by decisions made in the past, even though past circumstances may no longer be relevant.

Hyperbolic Discounting: explains the tendency to prefer smaller, immediate rewards over larger, later rewards.

Risk: involves the potential for losing something of value, weighed against the potential to gain something of value.

Reversibility: considers the ease with which a decision or action can be undone.

Overton Window: represents the range of policies politically acceptable to the mainstream population at a given time.

Compound Effect: describes how small, consistent actions over time can lead to significant outcomes.

Tipping Point: the critical point at which a minor change can lead to a major, irreversible effect.

Red Queen Effect: refers to the need for continuous adaptation and improvement to maintain relative performance.

Bayesian Updating: a statistical method for updating the probability for a hypothesis as more evidence or information becomes available.

Lindy Effect: suggests that the future life expectancy of some non-perishable items, like technologies or ideas, is proportional to their current age.

Pre-mortem: involves imagining that a project has failed to identify possible ways it could fail.

Scenario Planning: involves creating detailed and plausible views of how the future might unfold to guide current decision-making.

Exponential Growth: refers to the increase in quantity according to the exponential function, implying rapid growth.

Paradox of choice: states that having too many options can lead to decision paralysis and dissatisfaction.

Parkinson's Law: states that work expands to fill the time available for its completion.

Hofstadter's Law: notes that tasks always take longer than expected, even when Hofstadter's Law is taken into account.

Pareto Principle: suggests that roughly 80% of effects come from 20% of the causes.

Satisficing: involves choosing an option that meets a minimum threshold of satisfaction rather than the optimal solution.

Scoring & Decision Matrix: tools used to evaluate and prioritize a list of options based on a set of criteria.

Portfolio: refers to managing a collection of projects or investments to achieve strategic objectives.

Milieu: a sociological model that segments society into distinct groups based on shared values, lifestyles, and social status to better understand consumer behavior and social dynamics.

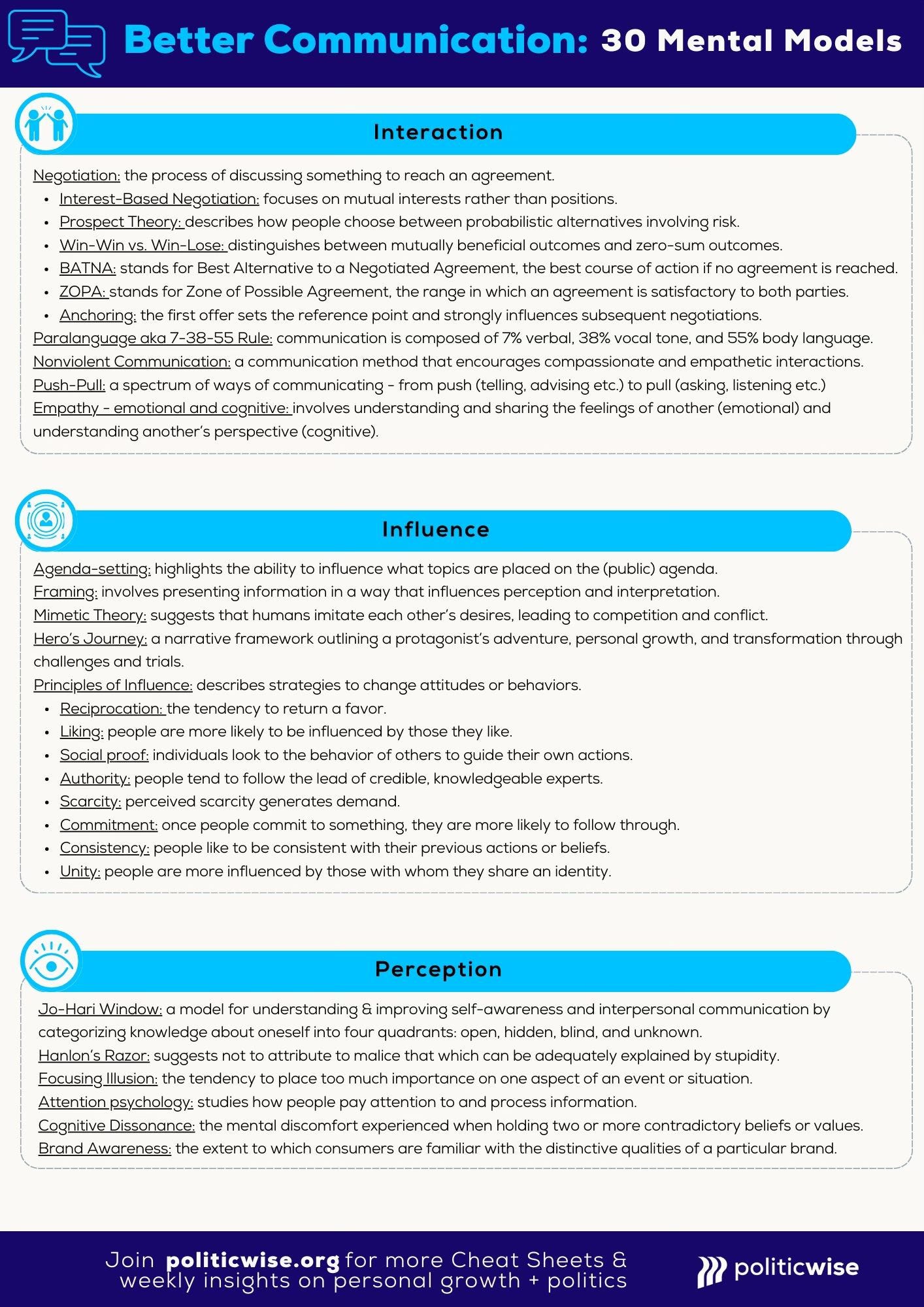

30 Mental Models for Communication

Agenda-setting: highlights the ability to influence what topics are placed on the (public) agenda.

Framing: involves presenting information in a way that influences perception and interpretation.

Mimetic Theory: suggests that humans imitate each other's desires, leading to competition and conflict.

Principles of Influence: describes strategies to change attitudes or behaviors.

Reciprocation: the tendency to return a favor.

Liking: people are more likely to be influenced by those they like.

Social proof: individuals look to the behavior of others to guide their own actions.

Authority: people tend to follow the lead of credible, knowledgeable experts.

Scarcity: perceived scarcity generates demand.

Commitment: once people commit to something, they are more likely to follow through.

Consistency: people like to be consistent with their previous actions or beliefs.

Unity: people are more influenced by those with whom they share an identity.

Hanlon's Razor: suggests not to attribute to malice that which can be adequately explained by stupidity.

Focusing Illusion: the tendency to place too much importance on one aspect of an event or situation.

Attention psychology: studies how people pay attention to and process information.

Cognitive Dissonance: the mental discomfort experienced when holding two or more contradictory beliefs or values.

Brand Awareness: the extent to which consumers are familiar with the distinctive qualities of a particular brand.

Negotiation: the process of discussing something to reach an agreement.

Interest-Based Negotiation: focuses on mutual interests rather than positions.

Prospect Theory: describes how people choose between probabilistic alternatives involving risk.

Win-Win vs. Win-Lose: distinguishes between mutually beneficial outcomes and zero-sum outcomes.

BATNA: stands for Best Alternative to a Negotiated Agreement, the best course of action if no agreement is reached.

ZOPA: stands for Zone of Possible Agreement, the range in which an agreement is satisfactory to both parties.

Anchoring: the first offer sets the reference point and strongly influences subsequent negotiations.

Paralanguage aka 7-38-55 Rule: suggests that communication is composed of 7% verbal, 38% vocal tone, and 55% body language.

Nonviolent Communication: a communication method that encourages compassionate and empathetic interactions.

Push-Pull: a spectrum of ways of communicating - from push (telling, advising etc.) to pull (asking, listening etc.)

Hero's Journey: a narrative framework outlining a protagonist’s adventure, personal growth, and transformation through challenges and trials.

Jo-Hari Window: a model for understanding & improving self-awareness and interpersonal communication by categorizing knowledge about oneself into four quadrants: open, hidden, blind, and unknown.

Empathy - emotional and cognitive: involves understanding and sharing the feelings of another (emotional) and understanding another's perspective (cognitive).

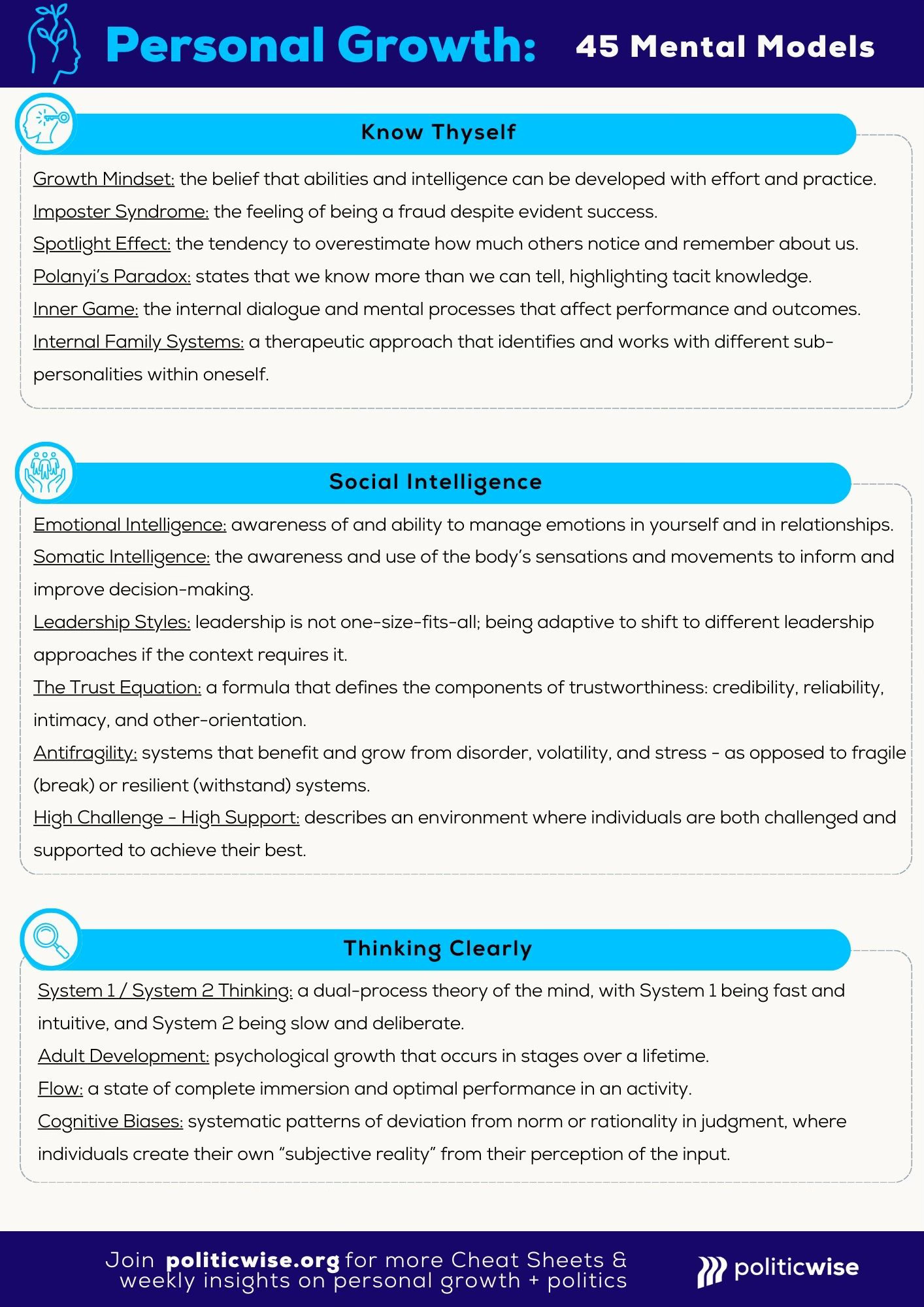

45 Mental Models for Personal Effectiveness

Growth Mindset: the belief that abilities and intelligence can be developed with effort and practice.

Emotional Intelligence: awareness of and ability to manage emotions in yourself and in relationships.

Adult Development: psychological growth that occurs in stages over a lifetime.

System 1 / System 2 Thinking: a dual-process theory of the mind, with System 1 being fast and intuitive, and System 2 being slow and deliberate.

Antifragility: systems that benefit and grow from disorder, volatility, and stress - as opposed to fragile (break) or resilient (withstand) systems.

Somatic intelligence: the awareness and use of the body's sensations and movements to inform and improve decision-making.

Internal Family Systems: a therapeutic approach that identifies and works with different sub-personalities within oneself.

Flow: a state of complete immersion and optimal performance in an activity.

High Challenge - High Support: describes an environment where individuals are both challenged and supported to achieve their best.

Leadership styles: leadership is not one-size-fits-all; being adaptive to shift to different leadership approaches if the context requires it.

Spotlight Effect: the tendency to overestimate how much others notice and remember about us.

Imposter Syndrome: the feeling of being a fraud despite evident success.

Polanyi's Paradox: states that we know more than we can tell, highlighting tacit knowledge.

The Trust Equation: a formula that defines the components of trustworthiness: credibility, reliability, intimacy, and other-orientation.

Inner Game: the internal dialogue and mental processes that affect performance and outcomes.

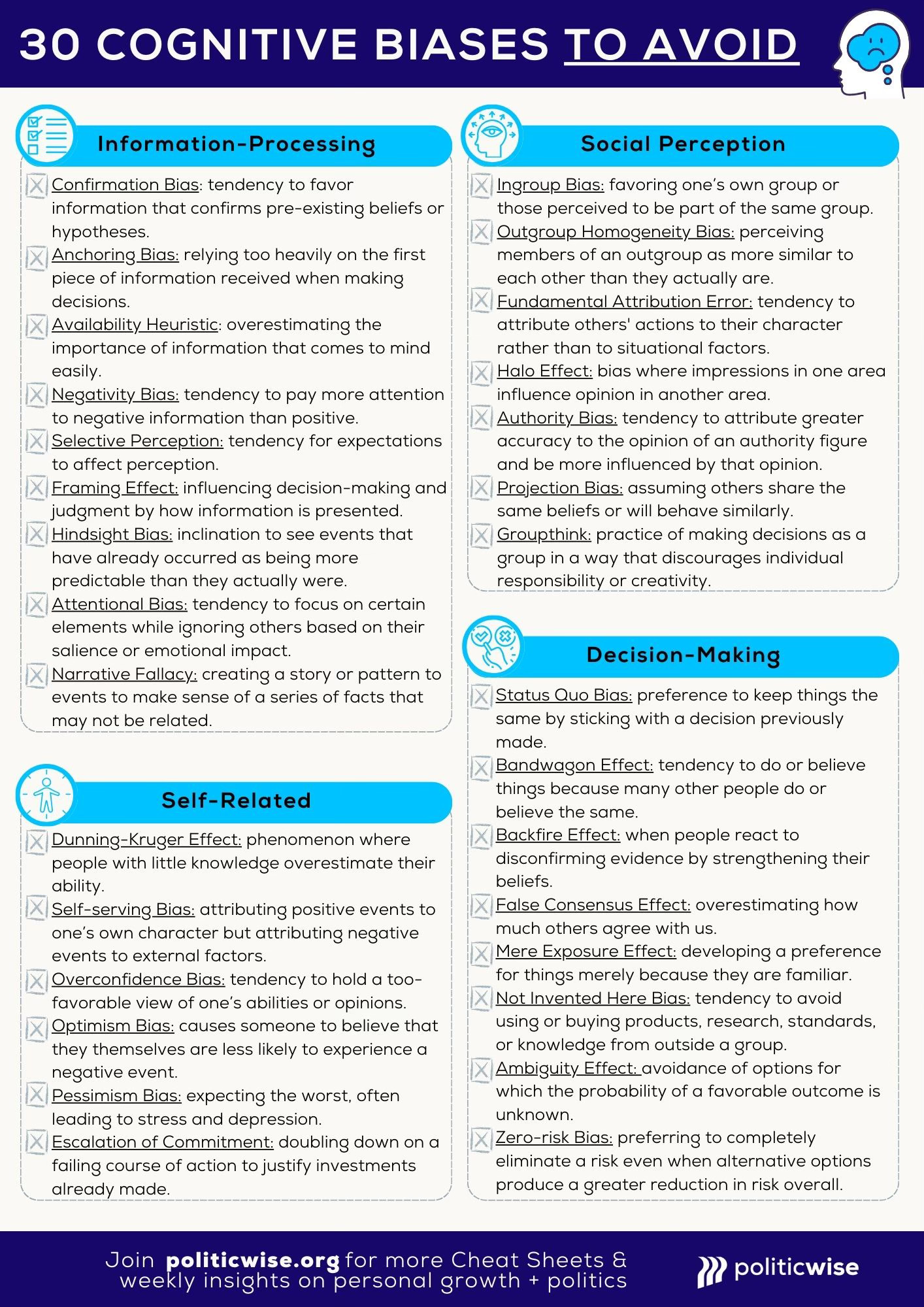

Cognitive Biases: systematic patterns of deviation from norm or rationality in judgment, where individuals create their own "subjective reality" from their perception of the input.

Information-Processing Biases:

Confirmation Bias: tendency to favor information that confirms pre-existing beliefs or hypotheses.

Anchoring Bias: relying too heavily on the first piece of information received when making decisions.

Availability Heuristic: overestimating the importance of information that comes to mind easily.

Negativity Bias: tendency to pay more attention to negative information than positive.

Selective Perception: tendency for expectations to affect perception.

Framing Effect: influencing decision-making and judgment by how information is presented.

Hindsight Bias: inclination to see events that have already occurred as being more predictable than they actually were.

Attentional Bias: tendency to focus on certain elements while ignoring others based on their salience or emotional impact.

Narrative Fallacy: creating a story or pattern to events to make sense of a series of facts that may not be related.

Social Perception Biases:

Ingroup Bias: favoring one’s own group or those perceived to be part of the same group.

Outgroup Homogeneity Bias: perceiving members of an outgroup as more similar to each other than they actually are.

Fundamental Attribution Error: tendency to attribute others' actions to their character rather than to situational factors.

Halo Effect: bias where impressions in one area influence opinion in another area.

Authority Bias: tendency to attribute greater accuracy to the opinion of an authority figure and be more influenced by that opinion.

Projection Bias: assuming others share the same beliefs or will behave similarly in a certain way.

Groupthink: practice of making decisions as a group in a way that discourages individual responsibility or creativity.

Self-related Biases:

Dunning-Kruger Effect: phenomenon where people with little knowledge overestimate their ability.

Self-serving Bias: attributing positive events to one’s own character but attributing negative events to external factors.

Overconfidence Bias: tendency to hold a too-favorable view of one’s abilities or opinions.

Optimism Bias: bias that causes someone to believe that they themselves are less likely to experience a negative event.

Pessimism Bias: expecting the worst, often leading to stress and depression.

Escalation of Commitment: doubling down on a failing course of action to justify investments already made.

Decision-Making Biases:

Status Quo Bias: preference to keep things the same by sticking with a decision previously made.

Bandwagon Effect: tendency to do or believe things because many other people do or believe the same.

Backfire Effect: when people react to disconfirming evidence by strengthening their beliefs.

False Consensus Effect: overestimating how much others agree with us.

Mere Exposure Effect: developing a preference for things merely because they are familiar.

Not Invented Here Bias: tendency to avoid using or buying products, research, standards, or knowledge from outside a group.

Ambiguity Effect: avoidance of options for which the probability of a favorable outcome is unknown.

Zero-risk Bias: preferring to completely eliminate a risk even when alternative options produce a greater reduction in risk overall.

Three Books That Blew My Mind Open To Mental Models

1) Charlie Munger's "Poor Charlie's Almanack"

A compilation of Munger's wisdom on mental models, and the practical insights that flow from them on decision-making, investing, and life.

What's most powerful: the multidisciplinary approach, thinking beyond conventional boundaries.

2) Ray Dalio's "Principles"

The personal and professional principles that have guided Dalio's success as investor and founder of Bridgewater.

What's most powerful: encouraging you to craft your own principles and apply them systematically in the important decisions in your life.

3) Donald Hoffman's "The Case Against Reality"

Challenges how you perceive reality, arguing that our perceptions are more about survival than truth.

What's most powerful: although not specifically about mental models, it reinforces the perspective of using mental models as tools to handle reality.